The Expedition Summary 1913-1918

The Beginning

The inspiration of anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson, the Expedition was initially to be a continuation of work in the western Arctic begun during the Stefansson-Anderson Expedition of 1908-1912 and an exploration for unknown lands in the Beaufort Sea. Mindful of the sovereignty issues raised by the potential discovery of new islands in the Arctic, the Canadian government took over the Expedition and added a program of scientific research along the Canadian Arctic mainland coast.

The new objectives resulted in division into two parties: the Northern Party led by Stefansson, to explore north of the mainland, and the Southern Party, led by Dr. R.M. Anderson, an experienced arctic zoologist, to conduct research on the northern mainland. Two government agencies were assigned responsibility: the Department of Naval Service and the Geological Survey of Canada. It was to be a three-year expedition, employing fourteen scientists.

1913 Departure

In June 1913 the Expedition set out from Victoria, B.C., on the ex-whaler, Karluk, under the command of Captain Robert Bartlett. Two schooners, Alaska and Mary Sachs, were purchased at Nome, Alaska, to handle the increase in men and supplies due to the expanded objectives. Severe ice conditions along the north coast of Alaska entrapped Karluk and three other ships. The two smaller schooners were able to navigate in shallow water as far as Collinson Point, Alaska, where they overwintered. Stefansson left Karluk with five others to hunt caribou in September 1913.

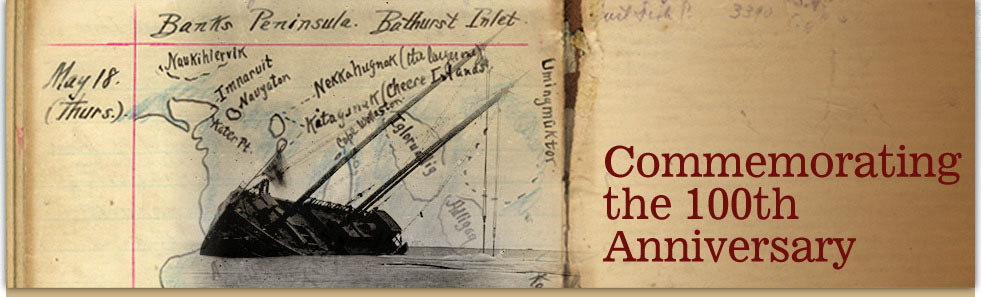

1914 Loss of the Karluk

Karluk drifted west with the pack ice, was crushed and sank in January 1914 near Wrangel Island off the Siberian coast. Although most of the 25 people on board reached Wrangel Island, four men were lost on the ice and four others died after reaching nearby Herald Island. After reaching Wrangel Island, Bartlett and Kataktovik crossed the ice to the Russian mainland and travelled east to Alaska to arrange the rescue. Three men died on Wrangel Island before they were rescued in the fall of 1914. Only one of the six scientists on the Karluk survived.

After the loss of the Karluk, Stefansson purchased the schooner North Star and new supplies, and hired local hunters, seamstresses, and ship's crews from several localities along the arctic coast to assist in the planned work of the Expedition.

The First Winter 1913-1914

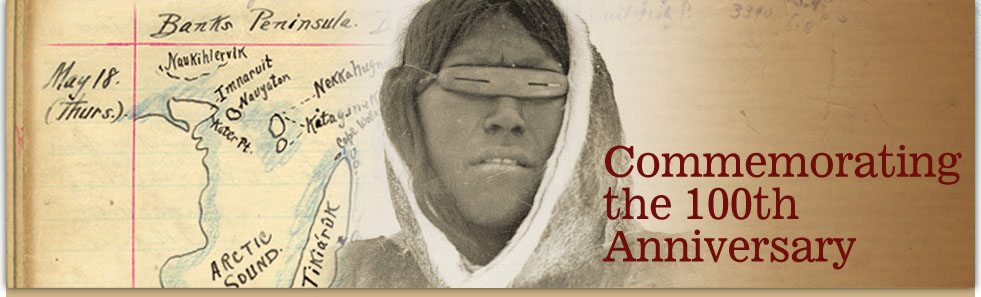

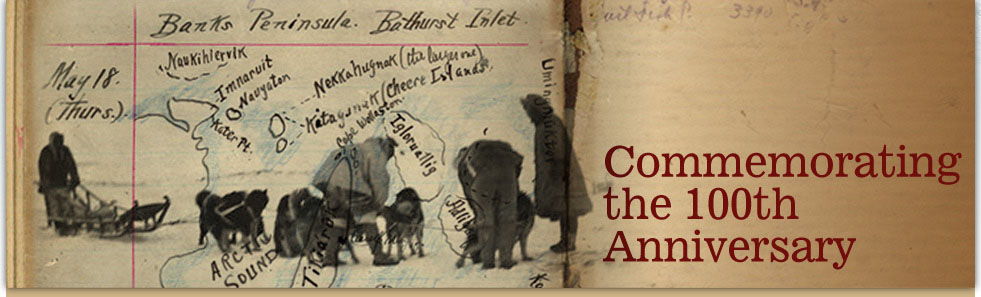

The men of the Southern Party spent the first winter at Collinson Point, learning to hunt, travel, drive dog teams, and making various scientific observations. Anthropologist Diamond Jenness excavated old Inuit settlements on Barter Island and studied the Mackenzie Inuit. In the late winter the topographers and geologist, Chipman, Cox, and O'Neill, completed contour and geological mapping along much of the coast from the international boundary, up the Firth River, and throughout the east and west channels of the Mackenzie River Delta.

In March 1914, Stefansson visited the Southern Party, announcing that he planned to use Mary Sachs, as well as some of the southern party's supplies and dogs, for his northern exploration. This led to considerable conflict between the two leaders, and between Stefansson and the other scientists, part of a series of disputes resulting from Stefansson's leadership of an expedition with two parties, two objectives, and two funding authorities giving instructions. Eventually Stefansson left with his ice party of three sleds, heading north over the Beaufort Sea ice to drift for several months before landing at Banks Island.

In the summer of 1914, the small Expedition schooners made their way along the coast to Herschel Island and eventually east to Coronation Gulf where a base was established at Bernard Harbour. These schooners were the first ships to carry the Canadian flag along the western arctic coast.

Wilkins, the Expedition photographer, took Mary Sachs to Banks Island in August with supplies for Stefansson's Party. Stefansson and his three men landed on Banks Island in late June after 96 days and 500 miles of travel over the ice. They all spent part of the winter at the camp established by Wilkins near Cape Kellet before heading north again.

The Second Year 1914-1915

After a busy winter of preparation, Anderson, along with Jenness and marine biologist, Johansen, explored the lower Coppermine River in February 1915. Jenness then travelled to Victoria Island and lived with an Inuit family for several months. At Bernard Harbour, he acquired a fabulous collection of representative utensils, tools, weapons and clothing of the Copper Inuit, described their material culture, and made sound recordings of their songs.

As soon as severe winter conditions allowed travel in 1915, the Southern Party travelled east from Bernard Harbour to Bathurst Inlet by dogsled, umiak, and schooner. They surveyed and mapped copper-bearing rocks in Bathurst Inlet, collected hundreds of specimens, and explored, mapped, and named islands and rivers along the coast. Wilkins, Natkusiak, and North Star assisted the Southern Party before heading to the northwest coast of Banks Island.

Discovering New Lands 1915-1916

Meanwhile, travelling by dog sled over the sea ice and supporting themselves by hunting seals, caribou, and muskoxen, the men and women of Stefansson's Northern Party established winter camps on Banks and Melville Islands. From there smaller parties discovered Brock and Borden Islands. Stefansson purchased a fourth ship, the schooner Polar Bear, in August 1915 and tried to go north to Melville Island by sea but was forced to winter at Victoria Island.

The Northern Party continued work in the northern islands in 1916, starting off in late January and discovering Meighen Island in mid June. In August they explored their third "New Land," later named Lougheed Island, then retreated to the winter camp at Cape Grassy, Melville Island.

1916 Return to Ottawa

After wintering again at Bernard Harbour, the Southern Party scientists returned to Bathurst Inlet in March 1916 and completed their studies. With 27 people, 25 dogs, and tons of scientific cargo, Alaska left headquarters in mid July. The Southern Party discharged their local assistants at Baillie and Herschel Islands, and reached Nome in mid August. The scientists were back in Ottawa by October 1916, thus successfully completing the planned three-year expedition.

Reluctant Return 1917-1918

Stefansson, however, prolonged his stay in the Arctic, in spite of instructions to return. In March 1917 the Northern Party dog sleds again headed north from Melville Island to Borden Island and out into the sea ice, reaching a latitude beyond 80° north before scurvy forced a return in late April. Stefansson's support parties returned south to Polar Bear at Victoria Island where Storkersen mapped much of the Island's north coast.

Stefansson reached Banks Island again in August 1917. There he found Mary Sachs had been re-launched after three years on shore, but then abandoned and wrecked. Stefansson purchased the schooner Challenge and caught up to Polar Bear as she worked her way west in September. When Polar Bear ran aground on Barter Island, Alaska, on the way out to Nome, Stefansson took the opportunity to remain for the winter, and planned another Beaufort Sea ice trip. When illness prevented him from this undertaking, Stefansson headed south in 1918, leaving Storkerson in charge of the last ice party. Polar Bear and her crew reached Nome in September 1918. The five-month ice drift was completed in November, thus ending five years of exploration. Stefansson never returned to the Arctic.

The Friendly Arctic?

Although Stefansson's published narrative is entitled The Friendly Arctic, seventeen men died during the Expedition: eleven after Karluk sank, two members of the Southern Party, and four members of the Northern Party. Although Stefansson promoted the idea of living off the country, his exploration parties carried large amounts of food to supplement their hunting, and at times his men were reduced to eating old skins and rotting meat from long-dead muskoxen.

Accomplishments

The four islands discovered in 1915 and 1916 by Stefansson's Northern Party were the last major new islands discovered in the Canadian High Arctic, and the only major Canadian islands discovered by a Canadian expedition. The ice trips confirmed that "Croker Land" and "Keenan Land" did not exist and regular soundings established the nature of the polar continental shelf.

The Southern Party returned with thousands of specimens of animals, plants, fossils and rocks, thousands of artifacts from the Copper Inuit and other Eskimo cultures, and over 4000 photographs and 9000 feet of amazing movie film. All of this has laid the scientific foundation for knowledge of Canada’s North.

Impact

The impact of the Expedition was considerable and continues to this day. Inupiat hunters and seamstresses from Alaska moved into the Canadian Arctic. The Expedition hired many local people, trading for artifacts and specimens, introduced new tools and equipment, fox trapping was established as a local industry, and two of the Expedition schooners were left behind, forming a focal point for camps and settlements. Local assistants gained valuable experience and became important members of Arctic communities.

Fourteen volumes of scientific results and several popular accounts of the Expedition were published. Four books have been written on the Karluk disaster.